The killing of Ali Abdullah Saleh on December 4, 2017, has generated a wide range of comments on his important role in Yemeni politics. Alongside many of his predecessors throughout Republican Yemen, he died violently, reflecting the instability of the country. As president for 33 years, he was the longest serving ruler of Yemen since 1918, beating Imam Yahya by three years. By the time he was removed from the presidency in early 2012, there is no doubt that he personally had a determining influence on the main political characteristics of the country, while also playing a decisive, though lesser, role in both the economic and social transformations which fundamentally shaped the country in the last five decades. His involvement in the country’s disintegration in the last five years is also undeniable. Yemen’s social transformation, as well as its internal and international political and economic developments during the previous half century, are discussed in my book, Yemen in Crisis: Autocracy, Neo-Liberalism and the Disintegration of a state, published in October 2017. A few of these issues are highlighted below, with focus on Saleh’s role in the outcomes.

Among his main achievements, at least for those who believe Yemen to be a nation, was unification of the two previous states: Yemeni unity was an extremely popular slogan both in the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) and the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Each of the wars which opposed the two states in 1972 and 1979 ended in agreements to establish unity, largely ignored by their ruling regimes at the time. In the mid-1980s, potential conflict over recently discovered oil resources near their joint border alongside political and financial crises in each state were incentives which brought about unification in 1990, and Saleh became the Republic of Yemen’s first president. While he is today widely blamed for the full integration of the two states in a single polity, by contrast with the federal approach supported by the PDRY’s leaders, it must be recognised that he was the main engineer of unification at a time when southern leaders were weak. Until his death, Saleh claimed unification as his main achievement; one of his main objections to the federal state proposed by the transitional regime which succeeded him in 2012 was his suspicion that it was a step towards breaking up Yemen into smaller entities. He also contributed significantly to the current disintegration of the state by his actions since 2012.

Discussions about decentralisation which emerged in the years following unification were intended to address two main issues: first, the clash between the ‘federal’ view of unification supported by southerners and others at the time of unification, and second, the concurrence between Saleh’s and the neo-liberal agendas, opposed by many in the country. These concretised over the long and bitter debate surrounding the Local Government Law during the 1990s and the law issued was a compromise which satisfied few. Its implementation effectively concentrated power at the centre thanks to the regime retaining financial control in Sana’a and thus keeping the local authorities weak, with heavy responsibilities and without the means to carry them out. This coincided with external financiers’ decentralisation policies which also contributed to the gradual disintegration of the state. These disempowered central administrative institutions and encouraged privatisation by establishing and financing parallel institutions at the central level, as well as encouraging ‘community’ participation or profit-oriented enterprises in all sectors, including infrastructure, education, and health.

There is little doubt that the Saleh regime was autocratic, initially in the YAR and after the first two years of unification, in the Republic of Yemen. However, this needs to be qualified: Yemen was not a fully dictatorial autocratic state either in the mould of the neighbouring monarchies in the Arabian Peninsula, or in that of the one-party ‘republics’ such as Egypt and Tunisia. Yemeni ‘democracy’ was real though it was limited by the regime’s strategy of always ensuring a comfortable victory for Saleh’s General People’s Congress (GPC) at parliamentary and local elections. Saleh did use his security services to suppress opposition which appeared to be threatening his rule, but here again, his regime was by no means as brutal as some others in the region, although some militants and rivals were assassinated and others disappeared. Signs of increasing challenges to Saleh’s authority surrounded the rise of Islah in the first decade of this century and the real challenge of an independent candidate at the 2006 presidential election; these were initial indicators of the regime’s exhaustion and conflicts over local elections were more acute than over the national parliamentary ones. The year 2007 also saw the end of the close alliance with the Hashed Al-Ahmar family when its senior member, Shaykh Abdullah bin Hussain, died.

Saleh supported neo-liberal economic policies, not because of the rhetoric of its international promoters, but because they coincided with his own predatory approach to the country’s resources and his policy of ensuring that benefits were concentrated among his leading supporters and, in many cases, relatives and military allies. Insofar as neo-liberal economic policies, regardless of claims, favour the concentration of wealth and resources under the control of small groups, there was no tension between ‘development’ financiers and the Saleh regime: the international financial institutions were not concerned with the identity of beneficiaries. They sought the emergence of a group endorsing neo-liberalism, in particular openness to international trade, i.e. imports, the rise of the private sector and reduction of the public sector, whether in services or in production. Saleh ensured that his supporters were the main beneficiaries of most development and other investments, public and private.

Having been forced to give up the presidency by pressure from the popular opposition expressed in the 2011 popular uprisings combined with the increasingly bitter rivalry with other elements of the elite focused on the succession to the presidency, Saleh took up a disruptive political role. The GCC Agreement had allowed him to remain head of the GPC so he could influence developments behind the scenes. He did so by undermining the National Dialogue Conference, which was an important element of the transition and, eventually, by allying with his former enemy, the Houthi movement, to bring down his successor Hadi who, as far as he was concerned, had betrayed him. This eventually led to the full-scale civil war, now raging for 34 months, with the intervention of the Saudi-led coalition in support of the 2012 transitional regime. In this war, Saleh’s tense and difficult alliance with his erstwhile enemies finally collapsed when the Houthis used their increased strength to dominate and, eventually, kill him.

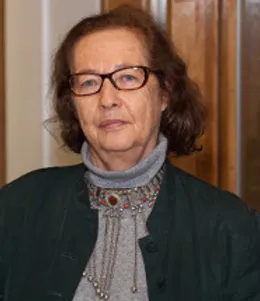

Helen Lackner has worked in all parts of Yemen since the 1970s and lived there for over 15 years during that period. She has written about the country’s political economy as well as social and economic issues. She worked as a freelance rural development consultant in Yemen and close to 30 other countries. Her new book, Yemen in Crisis: autocracy, neo-liberalism and the disintegration of a state, was published by Saqi books in October, 2017.